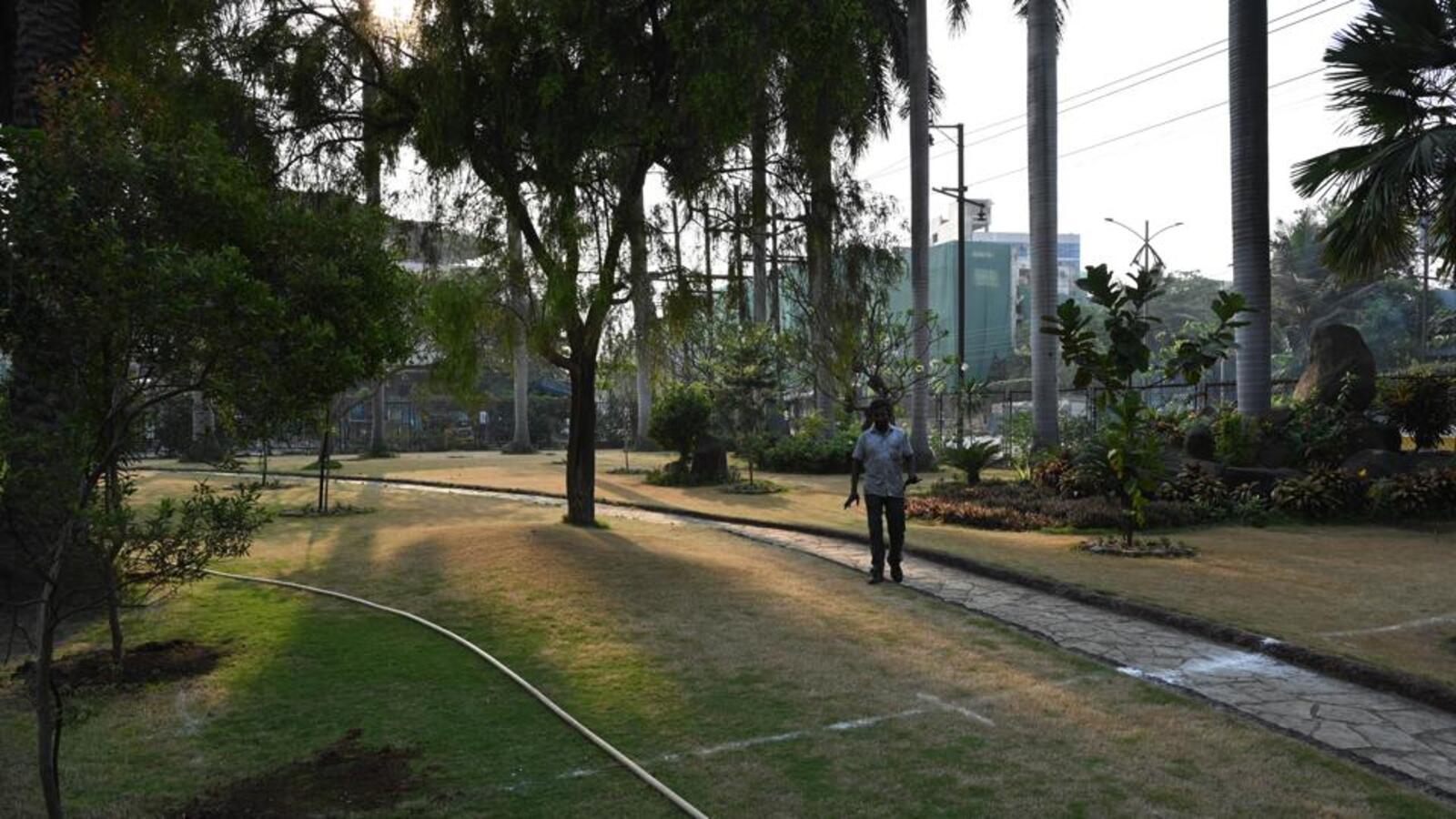

A 3.5-acre plot in Marol, once a sparse and sun-baked corner of Mumbai’s industrial heartland, has undergone a remarkable transformation into a thriving urban forest.

Developed jointly by municipal authorities, local industrial stakeholders, and climate-focused urban designers, the new green expanse is not just an aesthetic addition—it is already demonstrating its value in cooling down local temperatures by as much as 4°C. This green intervention, known as the Mahatapasvi Acharya Shri Mahashramanji Garden, has taken root in one of Mumbai’s more industrialised neighbourhoods, an area long flagged as an urban heat island due to its concrete-heavy, vegetation-scarce surroundings. In just over a year since plantation began, the site has proven that climate-resilient infrastructure—backed by scientific planning, native ecology, and public-private collaboration—can turn even the most barren urban spaces into environmental assets.

Backed by the District Planning and Development Committee, the initiative is a model for how adaptive reuse of urban land can contribute significantly to combating the effects of climate change in cities like Mumbai. The funding was mobilised to support both ecological regeneration and community access, bridging industrial utility with public purpose. The Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) oversaw the execution in coordination with the local cooperative industrial estate, with strategic input from a global environmental research body and ecological design consultants. In a city where tree cover is critically low and average summer temperatures continue to rise, the significance of this transformation goes far beyond aesthetics. Officials confirmed that the project’s core objective was to mitigate extreme micro-climatic conditions while increasing urban biodiversity. Recent temperature mapping conducted at the site by environmental researchers revealed that areas under dense canopy had ambient air temperatures averaging 32.7°C, significantly lower than surrounding zones, which peaked at 36.6°C.

The ecological design of the forest was key to its success. Landscape architects leading the initiative focused on cultivating a diverse and native plant palette, ensuring compatibility with Mumbai’s unique biodiversity profile. Drawing inspiration and specimens from the Aarey forest, Sanjay Gandhi National Park, and the historic Ranibagh Botanical Garden, the team planted over 100 species of trees, shrubs, grasses, and medicinal herbs. Indigenous varieties were favoured to ensure the survival and integration of the flora within the existing local ecosystem. Among the highlights are six species of bamboo and a mix of fruit-bearing trees like mango, jackfruit, banana, and papaya—chosen not only for their ecological roles but also to attract bird and butterfly species. The space already shows signs of new life, with increased sightings of native birdlife and pollinators, giving residents and workers in the area a much-needed daily connection with nature.

Officials involved in the planning and implementation noted that the project serves a dual purpose—cooling and community. “This is a living example of how collaborative governance and ecological knowledge can cool our cities while creating inclusive public spaces,” said a senior planning director present at the opening ceremony. She added that scientific documentation shared with the municipal authorities showed a clear year-on-year temperature reduction of 2°C in the greened patches, reinforcing the measurable benefits of such interventions. The strategic placement of the urban forest also ensures it functions as a natural buffer zone within the industrial ecosystem of Marol. Besides temperature regulation, the forest contributes to air purification, noise reduction, and stormwater absorption—key challenges in a densely packed metropolis. Equally significant is the way in which the green space integrates with the surrounding urban form, offering walking trails and resting areas for local citizens, workers, and families.

Officials stressed the importance of citizen participation in maintaining the momentum of such projects across the city. The success of the Marol project is already prompting discussions around replicability, particularly in other industrial and residential areas suffering from similar heat stress. “If scaled city-wide, these pockets of green can cumulatively bring down Mumbai’s average summer temperatures by 3 to 4°C over the next five years,” noted a civic environmental officer during the launch. Beyond environmental gains, this project also aligns with broader urban goals of equity and access. In a city where access to public green space remains unequally distributed, the forest in Marol has opened up a much-needed common ground for nearby communities. Positioned within a predominantly working-class and industrial area, it ensures that greenery is not a luxury but a basic right—helping to correct the spatial inequities embedded in urban planning.

Experts involved in the site monitoring have called the Marol urban forest a replicable template for climate-responsive planning. The scientific framework underpinning the design, which included biodiversity mapping and temperature benchmarking, will be submitted to the municipal corporation to inform future city-wide policies on green infrastructure. Urban planners also highlighted the potential for such projects to feed into larger state and national strategies around net-zero carbon goals and sustainable urbanisation. As climate risks intensify and urban heat waves become more frequent, the Marol urban forest demonstrates a critical shift in how Indian cities can future-proof themselves—not through massive technological overhauls, but through targeted, nature-based solutions that are both cost-effective and community-driven.

While Mumbai continues to grapple with the pressures of expansion, pollution, and population density, small-scale ecological interventions like the one in Marol offer a hopeful, green pulse. They represent a rethinking of urban development—one that prioritises resilience, inclusivity, and a return to the natural fabric that cities once emerged from. This forest, planted in the midst of warehouses and factory sheds, now sings with birdcalls and shimmers with fluttering wings—an emblem of how climate action, when rooted in local soil and powered by collective intent, can make cities not just liveable, but breathable.

Also Read : Yeida Allocates 13 Crore for Civic Development