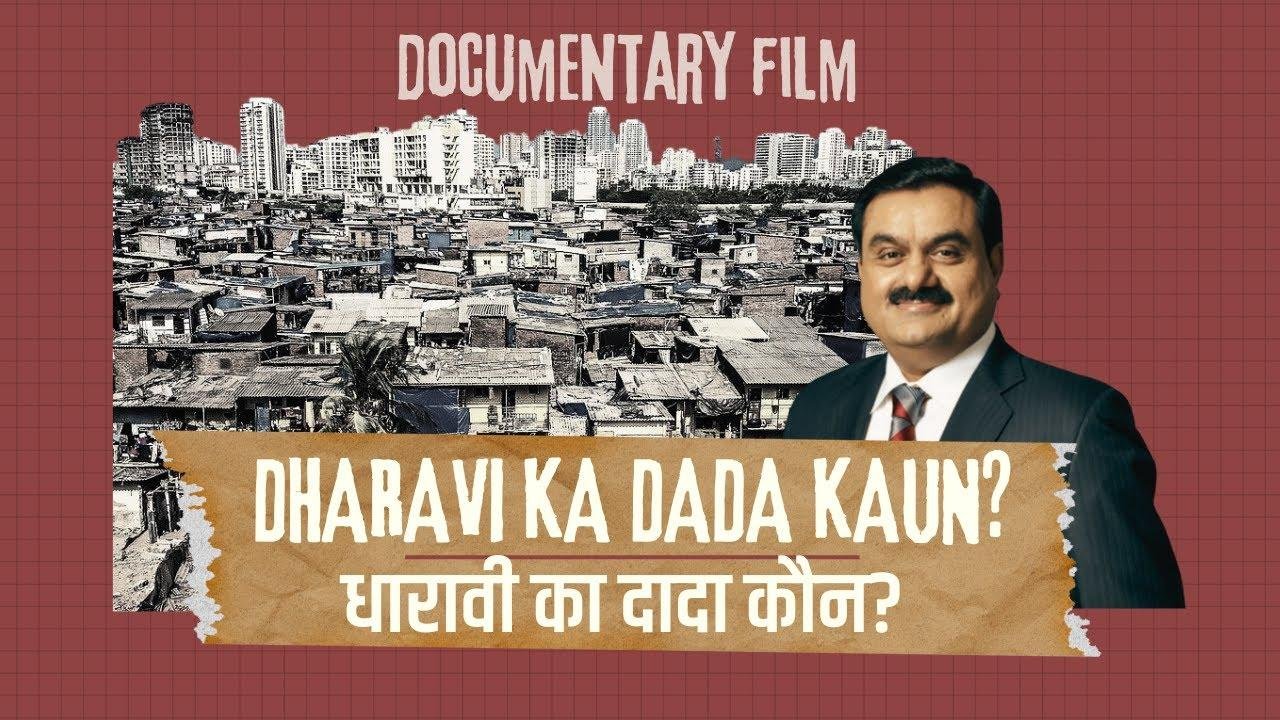

It was good to see the documentary film Dharavi Ka Dada Kaun by Paranjoy Guha Thakurta, a public-spirited journalist and television personality, at the Press Club in Mumbai on September 6. It features interviews with architects, activists, and visuals and also has some music and dance. We need many more such efforts, considering that the Adani-driven slum redevelopment project in Mumbai is seen as one of the most sinister land grab projects that will deprive us of most of our public land, leaving us gasping for breath.

Hundreds of acres of our land will be taken over mainly for housing for the wealthy in the name of slum redevelopment. High-rise buildings for the poor have failed everywhere, see the official inquiry indictment last week of the Grenfell towers fire in London which killed 72 poor residents. There is a strong similarity between the corruption and callousness of contractors there and in our projects here.

It is very much possible to create a humane redevelopment in Dharavi as numerous planners from Norman Foster and Charles Correa to P.M. Apte have suggested. It needs some restructuring, not demolition. Dharvi’s positive features have been praised worldwide. Many cities are trying to create communities where people live and work in the same locality without need for travel long for work from homes. Dharavi, with all its limitations, has many positive features, massive employment generation without any government support, environment friendly recycling and so on. The hideous land grab is cloaked in the name of aesthetics, beauty. It is said that Dharavi is ugly. I have walked through some parts of Dharavi, the entire area is certainly not a slum, there are large pockets which are in fairly good shape. There are problems of sanitation in some areas but these can be solved. Actually, it can be argued that actually that the so-called posh buildings being currently built in Mumbai and elsewhere are ugly, they are there for every one to see with a naked eye. From the street at the eye level you seen nothing but ugly car parks, no human beings can be seen in the buildings. I see that daily during my walks.

I met Neera Adarkar, a socially conscious architect yesterday, she is involved as an expert on many community projects. She told me that when Gautam Chatterjee, bureaucrat, was in charge of housing, the Norman Foster proposal made many good suggestions for redevelopment. Foster is a leading architect in the world. Every day, the government boasts of new development projects that are, in fact, a disaster for common people. The latest assault is a proposal to lay a track for pod cars between Bandra East Station and the Bandra Kurla complex. The pod cars will be beyond the pockets of most travellers. Already, life is awful there, everyone can see that, public transport is poor, repeat, poor. The new track will disrupt lives for years. If the authorities cannot do any good, why are they creating such hardships for the masses? The pod car project has few takers worldwide, yet our authorities want to impose it here. And for sure, it will not at all solve the traffic congestion problem in BKC for which the authorities must take all the blame.

Norman Foster’s proposal aimed to raise the quality of housing, sanitation, and public space in Dharavi, one of the world’s largest slums without major dislocation, without land grab. It is not that there are no problems. Current standards of sanitation are low, with just one toilet per 1,400 people, and the lack of open space means that the only places for children to play are in cemeteries and on the railway tracks. Our team spent time studying the way that the space was used and engaged with the local community – the residents of Dharavi recycle 80 per cent of Mumbai’s waste. We developed a comprehensive plan to improve the quality of life for all living there, which was based around the existing balance between spaces for living and working, yet introduced new public facilities and infrastructure. While we sadly have not had the opportunity to implement our master plan, this work has been a valuable reference for potential future projects. Significantly, it pointed the way to solutions in which the community would be respected and the quality of amenities transformed. This is a radical alternative to the traditional approach of bulldozing, uprooting the social structure, and starting afresh – a policy which has so far failed.

Even as the ongoing survey work to determine the eligibility of Dharavi residents for housing in the proposed redevelopment project is yet to be completed, Adani Realty, the project contractor, has sought an additional 552 acres of land in Mumbai’s eastern suburbs, a government official, related to the project, confirmed. He said the parcel of land is primarily owned by the Collector, Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC), and the Salt Pan Commission of India, and the land sought by Adani Realty includes 21 acres in Mother Dairy Kurla, 200 acres in Deonar, 250 acres of salt pan land in Bhandup-Kanjurmarg, and 64 acres in Mulund owned by the BMC.

The additional land will be used to relocate ineligible Dharavi residents, who will be housed in the newly developed “Nav Dharavis” (New Dharavis), Indian Express reported. Dharavi pulsates with intense economic activity. Its population has achieved a unique informal “Self-Help” urban development over the years without any external aid. It is a humming economic engine. The residents, though bereft of housing amenities, have been able to lift themselves out of poverty by establishing thousands of successful businesses. A study by the Center for Environmental Planning & Technology indicated that Dharavi has close to 5,000 industrial units producing textiles, pottery and leather.

Productive activity takes place in nearly every home. As a result, Dharavi’s economic activity is decentralized, human-scale, home-based, low-tech and labour-intensive. This has created an organic and incrementally developing urban form that is pedestrianized, community-centric, and network-based, with mixed-use, high-density, low-rise streetscapes. This is a model many planners have been trying to recreate in cities across the world for services like recycling, printing, and steel fabrication. Modern buildings are mostly assemblies of factory-made packages, which get thrown together on building-site blind dates. “Stop all the architects now”, fulminated the critic Ian Nairn in the Guardian in 1966, one could say the same about some builders in India. Grenfell Towers should be a warning for our ruling class. Seven years after flames engulfed Grenfell Tower, a public housing block in West London, killing 72 people, a public inquiry blamed unscrupulous manufacturers, a cost-cutting local government and reckless deregulation for the disaster, Britain’s worst residential fire since World War II.

The 1,671-page final report laid out a litany of corner-cutting, dishonest sales practices, incompetence and lax regulation that led to the tower being wrapped in cheap flammable cladding, which, after it caught fire in the early hours of June 14, 2017, quickly turned the building into an inferno. Many of the causes laid out in the report were documented in months of testimony before the inquiry, which was chaired over a seven-year period by a retired judge, Martin Moore-Bick.

But the report painted a damning picture of a Conservative-run local council, eager to reduce costs, working with careless, acquiescent contractors who installed combustible cladding panels, purchased from suppliers who knew they should never have been used in a high-rise building. Can the Dharavi redevelopment promoters assure us that such mistakes will not be repeated in the re-housing of ordinary people now living in Dharavi?

Disclaimer: The views expressed in the content article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Urban Acres or other associated parties.