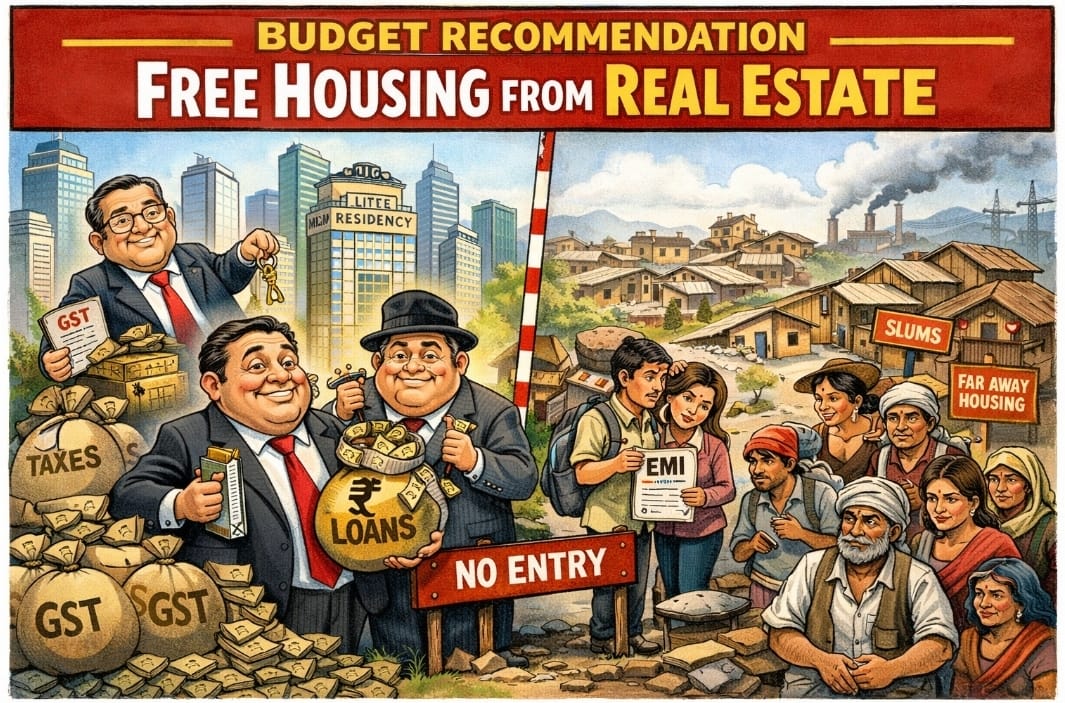

Free Housing from Real Estate

An Open Budget Recommendation To Hon. Finance Minister of India.

Madam Finance Minister,

This budget arrives at a moment when India’s homebuyers are no longer merely anxious about affordability—they are questioning whether cities are still meant for them at all. For decades, citizens were told that owning a home was the ultimate marker of stability. They followed the rulebook: education, employment, savings, taxes, restraint. What they encounter today instead is a system where buying a home has become the most financially and emotionally destabilising decision of their lives.

This is not accidental. It is structural. Housing in India has been absorbed into real estate, and once that happened, the idea of shelter quietly gave way to the logic of markets. Homes began to be priced like assets, cities began to behave like products, and homebuyers were reduced to balance-sheet participants whose patience could be stretched indefinitely. The most visible consequence of this shift is that developers now drive urban growth. They decide where cities expand, which locations receive infrastructure, and what price levels define eligibility. Entire neighbourhoods are shaped around “ticket sizes,” not around livelihoods. Communities are curated through affordability filters. Inclusion is decided at the launch price.

This is not urban planning. It is market-led segregation. What makes this more troubling is that the state has gradually withdrawn from its role as the primary shaper of cities while remaining deeply invested in the outcome. Governments today earn more from housing transactions than almost any other urban activity. When stamp duties, GST, development premiums, infrastructure charges, approval fees, and local levies are combined, between forty and fifty percent of the price of a home is collected by the state.

Homebuyers feel this instinctively. They may not know the line items, but they know the outcome: every home is priced beyond reach not just because of construction costs, but because housing has become a fiscal engine. This creates a profound contradiction. The same state that speaks of affordable housing depends on rising prices for revenue. The same planning apparatus that should protect inclusion benefits from exclusion. The government, unintentionally but undeniably, has become the largest silent stakeholder in unaffordable housing.

Banks complete this structure by locking citizens into lifelong debt. A homebuyer today begins paying interest before receiving possession. They absorb delays they did not cause. They carry risk they cannot control. They service loans for decades while developers and institutions exit early with certainty. For the buyer, ownership is no longer security. It is vulnerability stretched over twenty-five years.

The emotional cost of this system is never captured in budget documents. It lives in postponed marriages, delayed children, dual burdens of rent and EMI, parents aging without certainty, and a constant fear of disruption. Homebuyers are not speculative actors—they are exhausted participants in a system that treats their need for shelter as leverage.

This has now translated into a visible urban divide. India’s demographic profile is shifting rapidly. Cities are younger, but less secure. Middle-income households are being pushed farther from employment centres. Essential workers are being excluded from formal housing altogether. Peripheral settlements are growing faster than infrastructure. Urban India is becoming wealthier at the core and poorer at the edges.

This is not organic growth. It is policy-driven displacement. Madam, this budget must recognise that housing is no longer just an economic sector—it is a social determinant. When developers decide who lives where, when governments profit more from expensive homes, and when banks convert shelter into lifelong debt, cities stop being collective spaces. They become markets that filter people out. This is the critique that must be acknowledged. Incremental tax tweaks or additional schemes will not correct a system whose incentives are misaligned at the foundation. What is required is a philosophical reset: housing must be freed from real estate.

Freeing housing from real estate does not mean ending development. It means ending the domination of housing by profit logic alone. It means restoring housing to the domain of social infrastructure—where planning precedes projects, where risk is shared rather than exported to citizens, and where the state steps back from extracting revenue at the cost of inclusion. Homebuyers are not asking for charity. They are asking not to be punished for wanting a home. A city that treats its citizens as collateral may grow fast, but it will not remain stable. This budget has the opportunity to acknowledge that truth—not as rhetoric, but as intent. To free housing from real estate is to choose cities that belong to people again.