In a significant move to tackle the rampant problem of illegal hoardings across Mumbai, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) successfully removed 1,963 hoardings from the city’s 24 administrative wards on Saturday. This action follows a stern reprimand from the Bombay High Court (HC), which criticised both the Maharashtra government and municipal bodies for their failure to enforce regulations curbing the unchecked proliferation of political banners and advertisements.

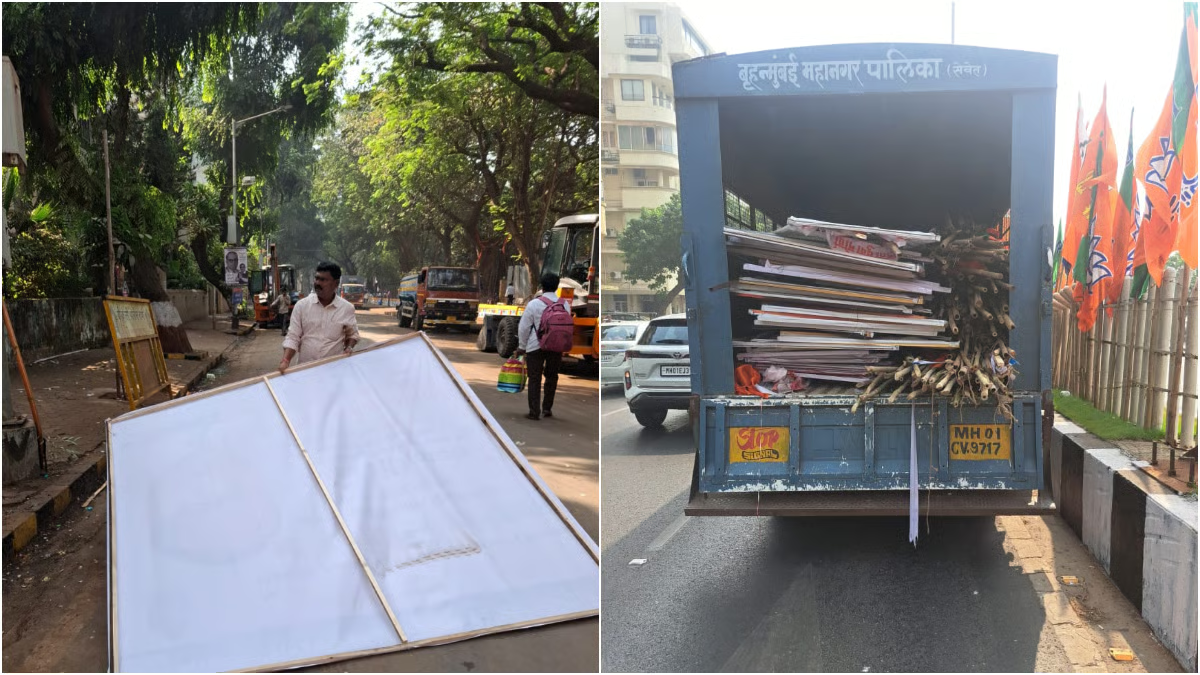

The spike in political hoardings coincided with the recently concluded state assembly elections, during which the city’s streets were overwhelmed by posters, banners, and flags put up by various political parties. Even after the elections, the city continued to bear the brunt of these unsolicited visual disruptions. In response to mounting public concern and legal pressure, the BMC launched a massive operation to clear these illegal structures from the city’s urban landscape. On Saturday, the civic body’s removal drive was extensive, targeting 204 boards, 367 banners, 12 posters, and 912 flags across key wards, with the highest number of removals in the ‘A’ ward, which encompasses prominent areas such as Fort, Churchgate, and the Chatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus (CST). These areas, being high-profile zones, are often the focus of political advertising and are among the first to receive attention in the BMC’s efforts to restore order.

Historically, the BMC has been involved in the removal of nearly 15,000 to 20,000 illegal hoardings annually. A significant portion of these hoardings—about 45%—are related to birthday wishes for political figures or festive displays. Despite these frequent operations, the BMC has faced criticism for not implementing a comprehensive policy to regulate outdoor advertisements. The absence of a clear framework has allowed political hoardings to proliferate, clogging up Mumbai’s urban spaces and violating public spaces. While the BMC’s recent crackdown addresses the immediate issue, critics point out that the absence of a well-defined ‘Outdoor Advertisement Display’ policy leaves the city vulnerable to further unregulated ad placements. This growing challenge highlights the urgent need for a structured and enforceable system that can balance public order with the need for legitimate advertising, especially as political campaigns continue to dominate public spaces during election seasons.

The recent removal drive, though commendable, is only a short-term fix to a persistent problem. Moving forward, the BMC must act decisively to formulate and enforce policies that ensure a clutter-free and well-regulated advertising environment in Mumbai. The political hoardings issue continues to be a glaring reminder of the city’s need for effective urban planning and governance in the face of growing urbanisation and political activity.